Containerization vis-à-vis Virtualization

While containerization technologies have been around for years – think Solaris Zones and FreeBSD jails – clearly they have been garnering a lot of attention lately. Throughout 2014, Docker gained significant momentum, with most major IT vendors announcing some kind of Docker partnership or strategy. Towards the end of the year, CoreOS, which previously had a tight partnership with Docker, announced they would be developing their own competing container technology called Rocket. Ubuntu has also jumped into the game with LXD, and our own EMC2 Federation has already been using containers for years. In fact, containers have been a core technology within Cloud Foundry since its inception within VMware in 2011.

So what’s all the buzz about?

What is a Container?

First things first: What is a container, and how is it different than a virtual machine?

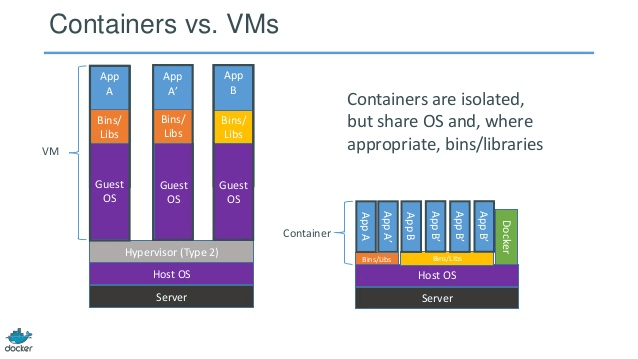

We’re all familiar with hypervisors at this point – the hypervisor provides full hardware virtualization, emulating compute, network, and storage resources for multiple Guest OSes running on a physical machine. The Guest OSes running in a VM are essentially the same as the equivalent OS running on a physical machine: they expect to be managing physical hardware, and they run all of the services necessary to do so – including an OS kernel, drivers, memory and process management, et cetera.

While this enables strong isolation between VMs, allows customers to increase the utilization of their hardware, and provides an environment that is compatible with most legacy workloads – there is a ton of effort duplication involved. Because each VM runs a full OS, the size of Virtual Machines is fairly large: typically tens of gigabytes. Each VM is also doing a lot of duplicate work, since each thinks it is exclusively responsible for managing physical hardware. Incidentally, this is the reason that storage deduplication works so well in VM environments: there’s a lot of duplication to remove.

On the other hand, containers share a single OS and kernel, as depicted in the right side of the diagram. Isolation between containers is achieved within the host kernel, which provides namespace segregation for compute, network, and filesystem resources, along with control groups (cgroups) to limit resource consumption. These are technologies that have been in the Linux kernel for years, but have been difficult for mere mortals exploit until now, with the advent of container management tools like Docker and Rocket.

Since containers share the host OS and kernel, they are much more lightweight than VMs. Applications running in containers run at bare metal speeds, and their footprints are typically measured in megabytes versus gigabytes. One way to think of containers relative to virtual machines is to think of them as providing process/application virtualization, rather than OS virtualization.

Another benefit of containers over virtualization is startup time. Virtual Machines tend to take a while to start up, because the application can’t start until the Guest OS boots. At best, you’re probably looking at double-digit seconds. Containers, on the other hand, generally start in milliseconds – because the OS/kernel is already booted. This is one reason why live migration (e.g. Vmotion) is not a critical requirement for containers: if a container dies, restarting it is trivial.

On the other hand, containers lack some of the flexibility of virtual machines. With a hypervisor, you can run any x86/x64 OS you’d like within a VM. But since a container shares a single kernel with its host OS, you’re stuck with that kernel; you can’t run a Windows container on top of a Linux kernel. Containers, as a fledgling technology, are also much less mature and polished than their hypervisor counterparts. Security is another concern in the container world – because the kernel is shared, the attack surface is broader. If an attacker gains access to the shared kernel, he effectively has access to all containers on the host.

Portability

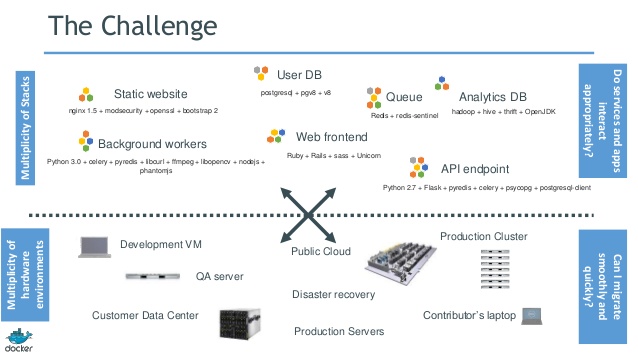

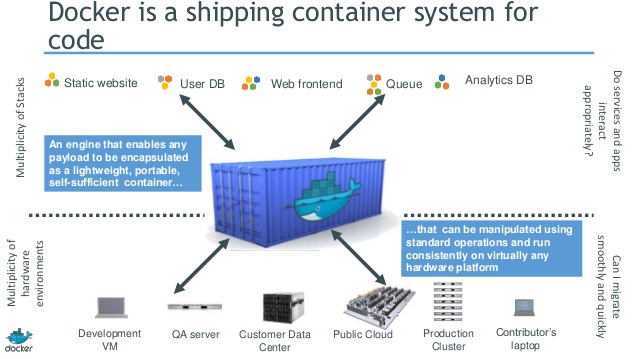

Containers allow applications, along with their dependencies (e.g. libraries and environmental state), to securely share a single OS in a lightweight, portable deployment model. This allows applications to be written on, say, a developer’s laptop, and then easily deployed onto a physical server, VM, or a private/public/hybrid cloud, without having to worry that the application will behave differently in production than in dev/test.

The challenge today is that, as much as we’d like dev and prod environments to be the same – they typically are not. OS distributions, patch levels, runtime environments, libraries, etc will tend to differ between environments. As such, the behavior of applications will tend to vary depending on where said applications are executed.

Containers aim to solve this problem.

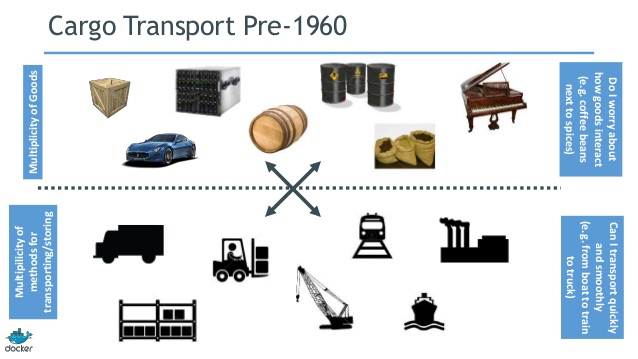

Consider the analogy of transporting physical goods. Prior to the development of shipping containers, this was a logistical nightmare. At the transport layer, there were (and are) multiple modes of transportation – cars, trucks, busses, cranes, etc. But the material to be transported varied wildly. Fitting a particular set of widgets into a given transport mechanism was Tetris gone amok.

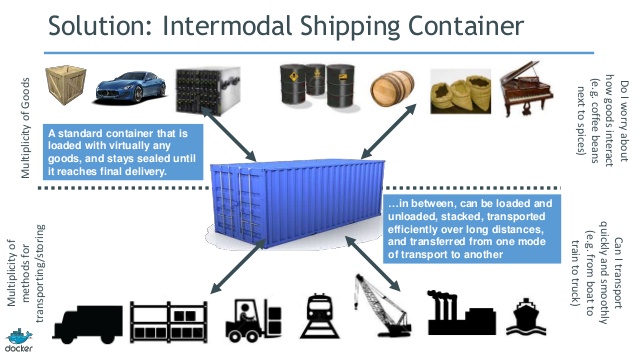

Enter shipping containers: an international standard for containerizing “stuff” to be transported from one place to another. The producers of said stuff just need to fit it into the container, and the transporters just need to ship the container, with no concern about its contents. Now the Tetris game consists entirely of those long rectangular pieces (they’re apparently called “Straight Polyominos,” in case you were wondering).

Containers in the IT world parallel those in the shipping world: developers package their applications in containers, which house all of the stuff necessary to run a particular application instance. Operations then works outside of the containers, ensuring that they run in a stable environment, and that they are distributed accordingly throughout the compute fabric. As such, containers are an enabling technology for DevOps, allowing for a smooth transition between development concerns and operations concerns.

“Containers vs. Hypervisors”

Some in the industry have predicted that the rise of containers will mean the end of hypervisors. I would maintain that this declaration is premature. There are and will remain use cases for both technologies – and in some cases, both may be used together.

Virtual Machines will continue to be the solution for entrenched platform two applications with monolithic architectures (for example, traditional relational databases). Virtual Machines will also continue to be the choice for applications that have been written on OSes that don’t have container implementations (for example, Windows – for now).

Containers will be the solution for new, platform 3, distributed applications that employ micro-service architectures. These containers may run on bare metal compute fabrics that are built for the express purpose of running containers – for example, CoreOS or Kubernetes clusters. But containers may also run within existing IaaS stacks (for example, AWS EC2), which provision virtual machines rather than bare metal.

Using containers on top of IaaS stacks that use virtual machines can provide additional benefits. For example, the portability of containerized applications can improve mobility of applications between disparate clouds. Deploying containerized apps in existing hypervisor-based clouds can also allow containers to take advantage of the more mature network, storage, and security capabilities built into today’s hypervisor suites.

Clearly, any given enterprise will be running both platform 2 and platfom 3 (and often platform 1) applications simultaneously; and while it may be uncommon for a particular application to employ both virtualization and containerization, it will be quite common for a particular enterprise to use both technologies for their various workloads.

Distributed Applications

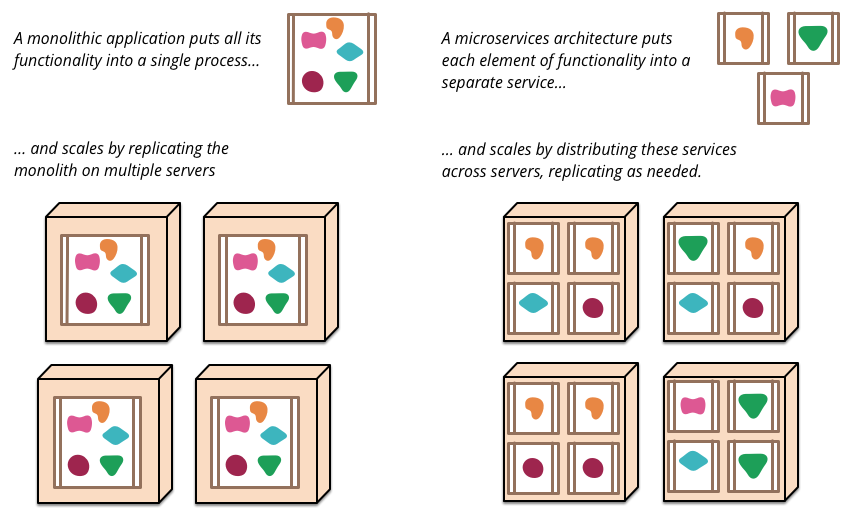

Containers are also an enabling technology for distributed applications, allowing software architects to develop service-oriented architectures at scale. Distinct from monolithic platform two applications, P3 apps tend to be decomposed into microservices, which communicate with each other via message busses (e.g. RabbitMQ) and/or REST APIs.

These microservices will often be deployed within containers, where each container houses one instance of a particular function. Multiple instances of a particular function are deployed within a compute fabric, which allows that aspect of the distributed application to be scaled horizontally – when more work needs to be done, more instances are created (on more hosts); when the workload decreases, instances are decommissioned. This scale-out microservice architecture also provides high availability: if a host running a particular instance/container dies, there are other instances that remain running on other hosts; and additional instances can be started in seconds.

Containers and The Federation

EMC II

Data services (e.g. Object, Block) in both ViPR and ECS are implemented within Docker containers. ViPR’s block implementation is actually ScaleIO running inside ViPR-managed Docker containers (NOTE: As of publication, ViPR and ECS no longer offer block services).

Other groups within EMC are also using container technologies: for example, the VPLEX Quality Assurance team uses Docker for their integration testing framework (Cloudrunner). When a VPLEX developer commits Geosynchrony code updates, Cloudrunner – which runs inside Docker containers – automates the process of compiling the new binaries, distributing them to a pool of Docker hosts, executing a suite of integration tests, and reports results. With Docker, they are able to dynamically scale the resources available in the pool of Docker hosts, increasing and decreasing test capacity on demand.

Mozy also makes heavy use of containers within their backend services infrastructure.

Pivotal

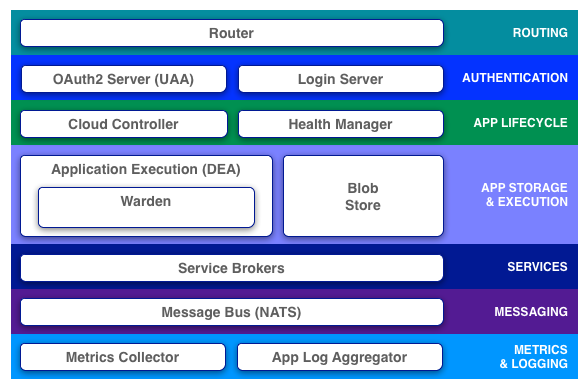

As previously noted, Pivotal CF (Cloud Foundry) launches applications within containers. Cloud Foundry’s Cloud Controller component schedules an application to run within a pool of Droplet Execution Engines (DEAs). The selected DEA is then responsible for creating a container for the new application, and for monitoring the application’s state over its lifecycle, in conjunction with HM9000 (CF’s Health Manager).

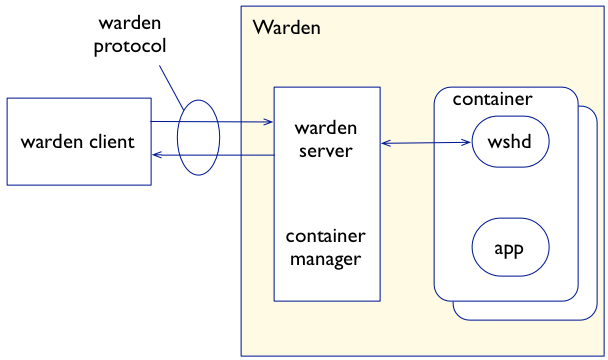

DEAs in the current release of Pivotal CF use Warden, a container management system developed by VMware and Pivotal. With Cloud Foundry Diego Project, Pivotal – along with IBM, SAP, and Cloud Credo – are rewriting the Cloud Foundry runtime. The purpose and details of Diego are outside the scope of this article, but a key point relative to the subject at hand is the switch from Warden to Garden for container management.

In Cloud Foundry today, each DEA host runs the Warden service, which implements both the Warden Server (the API), and the Warden container manager as one. This tight coupling of the Warden API and the container manager makes it difficult to implement alternative container technologies, as the entire Warden service must be updated, rather than just the container implementation itself.

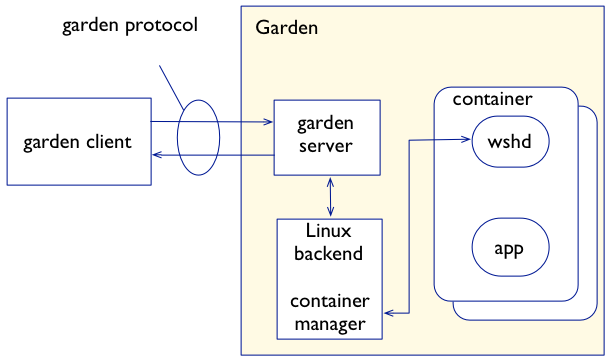

With Garden, Pivotal effectively separates the container management API from the container implementation itself. This is a common theme in distributed “third platform” applications – the separation, or decomposition, of application components into interconnected microservices. In this case, the Garden API will provide a standardized API for clients to manage containers, and various Garden backends can essentially “plug in” to the API, allowing different types of containers (e.g. Linux and Windows) to be managed via a standard interface. While Warden may or may not use Docker’s container implementation (libcontainer), it will leverage graphdriver (Docker’s storage provider) to allow Docker images to be pushed directly to Cloud Foundry.

VMware

VMware also recently announced several container-oriented initiatives.

Docker Machine is a new deployment mechanism for Docker hosts. Rather than an operator having to remotely login to a host and install the Docker daemon, Docker Machine provides a pluggable architecture to achieve this programatically and remotely. VMware has devloped Docker Machine plugins for VMware Fusion, vSphere, and vCloud Air.

Kubernetes is Google’s open source container orchestration, clustering, and scheduling framework. VMware has extended its existing Big Data Extensions (BDE), allowing Kubernetes clusters to be deployed within vSphere environments. Apache Mesos is similar to Kubernetes, and VMware is also leveraging BDE to deploy Mesos clusters within vSphere.

More recently, VMware announced Photon and Lightwave – A stripped down Linux distro for running containers, and an authorization and authentication platform for containers, respectively.

A Practical Use Case: Dockerized SYMCLI

AKA, an excuse for self-promotion

While this is by no means a typical use case for Docker or containers in general, it is a useful tool for those of us whose day-to-day lives are oriented towards classic EMC storage solutions.

Dockerized SYMCLI allows you to run multiple versions of SYMCLI in Docker containers on your own laptop. The primary use case for an EMC SE is to mine configuration data from offline Symmetrix/VMAX databases (SYMAPI and ACLX databases, specifically).

Previously, this was challenging because different Symmetrix models require different versions of SYMCLI – and only one version of SYMCLI can be installed on a particular OS instance. So running multiple versions of SYMCLI would require multiple VMs; all independently managed. This was fairly cumbersome and inelegant.

Dockerized SYMCLI does this with containers, which can be started, stopped, deployed, etc. very easily.

For more information, including the bits and installation instructions, please visit https://github.com/seancummins/dockerized_symcli.

Where to Learn More

- Docker Online Tutorial: https://www.docker.com/tryit/

- http://learningdocker.com/

- The Docker Book: Amazon, Author Page

- CoreOS Rocket

- Ubuntu LXD